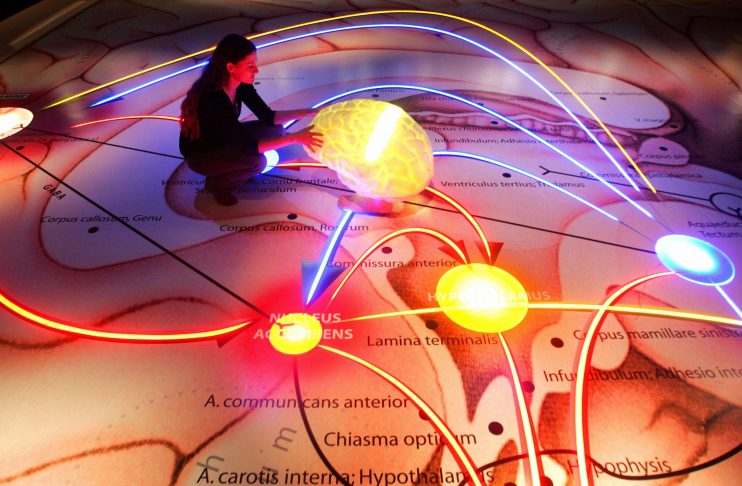

Technology has changed our minds — now it’s time for brands to catch up

Let’s begin with the pretty bold claim: that digital technology has altered us forever.

Over the past decade, an enormous amount of research and literature has been produced on the subject — from the American writer Nicholas Carr, to MIT professor of social psychology Sherry Turkle, to the eminent British neuroscientist Susan Greenfield.

Each in their own way details the physiological, social, and psychological impact that “always on technology” is having on our sense of self and our experience of the world.

As humans, our brains have an incredible level of neural plasticity which allows us to adapt to stimulus around us. We can see this in the way technology has been so quickly and effortlessly embedded into every part of our lives.

Yet it is questionable whether our brains have evolved fast enough to adapt to the torrent of information we consume. The continuous pings, messages, and content suggestions, coupled with pandemic Zoom culture, mean we are entering an unprecedented phase of hyperstimulation.

And while this is thrilling for our brains, psychologists worry that our devices are monopolising all our attention to the point that they are hampering our understanding of the world. As professional counsellor Casey Swartz warns: “We have entered into a situation where the gadgets we carry around us and the cognitive rhythm they dictate are pitted against the possibility of deep engagement or thorough encoding. They ask us to be anywhere but here, to live in any moment but now.”

Even the head of Google, Eric Schmidt, says he “worries that the level of interrupt, the sort of rapidity of information…is in fact affecting cognition.” Each day the Android mobile sends over 11bn notifications to its more than one billion users. It is easy to see mass scale disruption.

The real enemy of brand building

As marketing experts whose job it is to make it easy for people to encode brand ideas and associations in culture, we should be taking these warnings seriously. Because the more minds are deeply distracted, the less impact we can have on them. The less we get encoded in memory, the less we get talked about.

It feels like, as an industry, we have been so distracted by the race to keep up with the latest marketing technology, and the many iterations of social media platforms, we have ignored this momentous shift. We have been touting a new, revolutionary philosophy of consumer centricity, without really thinking about the human mind at the centre of this techno-culture.

It is tempting to believe that the pandemic-fuelled recession will be the biggest long-term consumer and business challenge ahead. But there is a strong argument to suggest that people’s decreasing ability to “focus” on information, combined with mass attention scarcity, will become the real enemy for brand building and growth.

DADD’s Army and the dopamine loop

We have put a name to this enemy. We call it “DADD”: Digital Attention Deficit Disorder.

This is not a medical condition, but a psycho-social phenomenon that affects us all. It’s a condition we all know intimately, whether we like to admit it or not. A deep feeling of not being able to settle in the moment. A constantly wandering, impatient mind, always running to the next thing, always afraid of missing out.

DADD feels like a deep itch, always there in the background, demanding to be satisfied, to be clicked, to be watched, to be responded to, over and over again. Our attention is pulled from one second to the next, always in the future, never in the now.

Research would suggest that the pandemic has only heightened and accelerated DADD sensations, because we are embedded in screen life more than ever. According to conservative estimates, we now spend on average around three to four hours a day on devices in the UK. That is the equivalent of around 50 days a year.

So, what happens precisely to consumers’ brains when they get over-stimulated by an unending stream of interruptive pings and content? According to esteemed neuroscientist Baroness Greenfield, they get stuck in a chemical reward loop, in which the brain starts to over-produce dopamine.

Simply put, too much dopamine inhibits the prefrontal cortex, which switches on the more “mindless” mode of the brain.

We become more driven by our senses, not by cognition. We become more emotional, more rooted in now. We have a lesser sense of self, we are over-reactive, and even have less empathy — not unlike like impatient children.

This is not to suggest that we are all in a permanent state of regress. We just need to be mindful that lengthy exposure to digital environments brings out certain cognitive and emotional reflexes and more instinctual behaviours that don’t appear when we are cut off from our screens.

The logic of creativity turned on its head

It’s easy to see this dopamine-fuelled brain at work, from the digital “snacks” it consumes on a second by second basis. Observing viewing statistics from all the major social platforms, cravings are for shorter and shorter messages, more off-beat humour, intense visuals, more rhythmic music, and even bigger emotional highs, all mixed in together.

The constant desire for more is also fuelling experimentation with new narrative formats, technologies, and even language. The collective creativity on the back of this has been astounding, breaking many of the conventions of traditional communications. TikTok notably promotes stories that have no beginning, middle or end.

We are in the midst of a huge creative revolution. But arguably, most brands other than the digital behemoths themselves have yet to fully take part in it and reap the rewards. They rarely make it onto the centre stage.

Why is this?

By playing the dopamine game, we lose control of brand

There is a notion that when becoming fully digital, one has to embrace the folly that goes with it, and somehow let go of your brand to the collective, embracing the full spectrum (pretty or not) of internet subculture, cute animals, gaffes, crazy influencers and memes to stay salient.

But designing experiences for people with DADD does not necessarily mean (in ex-Googler Tristan Harris’s words) that we have “to race to the bottom of the brain stem” and lose all brand integrity.

The over emphasis on technology interfaces and frictionless customer journeys over the last few years has led companies to neglect their core brand. (It is also why a plethora of services and products appear that all look and communicate in the same way.) But it is possible to be “sticky” without succumbing to the realm of quokka cuteness or becoming embroiled in conversations of identity politics.

A new approach

To counteract DADD and ensure brand salience in the digital environment, we are rethinking our whole approach. To own a space in the digital mind, brand “signals” must work harder than ever. The traditional logic of “storytelling” has been turned on its head — and creativity must be pushed to new limits.

We now design end-to-end brand experiences that are fully in sync with the behaviours and idiosyncrasies of the post digital mind. And in doing so, we ensure that our brands contain the right levels of stimulus — cultural, psychological, psychophysical — to become sticky and desirable.

Crucially, this means we look at the experience not as chain of seamless, frictionless connections, but instead a series of carefully orchestrated multi-sensory and psychological stimuli that keeps the brain fully engaged, and the brand deeply encoded in memory.

In the digital environment, overflowing with hyperstimulation, brands need to work so much harder to be themselves, and the cues have to be so much stronger — on both conscious and subconscious levels.

Technology has changed our minds. It’s time for brands to catch up.

Main image credit: Getty