Great expectations: The Darwinian wars of economic and epidemiological forecasting

A key concept in modern economics is, to use the jargon term, rational expectations.

The idea has dominated orthodox macroeconomics over the past 30 years. Not all economists have been persuaded of its merits by any means, but nevertheless, its influence has extended far beyond academia, into finance ministries and central banks around the world.

The basic idea is simple, even though the maths of the macroeconomic models which use rational expectations can rapidly become hair-raising.

When forming a view about the future, an individual chooses the model which best describes how the economy works. It is then simply a matter of running the model and using the values which it outputs as your expectations.

An obvious criticism seems to be that economic forecasts are very often wrong, but this is easily handled by the rational expectations enthusiasts. Each individual forecast in a sequence of months or years can be wrong. The key thing is that the errors over time cancel out. On average over time, the forecasts are correct.

The idea is not as absurd as it may appear to the layperson. For example, the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia has published the Survey of Professional Forecasters since 1968.

This does what it describes on the label. It takes a wide range of forecasts by academic, commercial, financial and governmental bodies. Information on the average forecast for, say, GDP growth one year ahead is published, as well as details of the spread around the average.

Remarkably — and exactly in line with rational expectations — comparing the predictions with the actual growth over many years, the errors do indeed balance out. Spectacular errors have been made for individual years, but the over and under-predictions cancel out over time.

A more telling attack is that economists themselves do not seem to agree on what constitutes the correct model of the macroeconomy. Different groups have different models.

The standard defence is that the best model will eventually prove its superiority and will drive the others out of existence. But the problem here is that this has just not happened.

The concept of rational expectations can be applied directly to the predictions of the epidemiological models. These purport to describe how a virus spreads. So to form a view about the future, make a set of assumptions about the key inputs, and use the forecasts generated by the model.

It should be much easier in epidemiology for the best model to eliminate its competitors than it is in economics. Economics has a wide range of variables to predict, such as inflation, GDP, unemployment, public borrowing, interest rates. The focus of epidemic predictions is much narrower and their models are in general mathematically simpler than those of economics.

The Covid pandemic set up a competition between epidemiological modelling groups of fierce Darwinian intensity. The efforts of many years of academic debate have been concentrated into a handful of months.

But no group seems to have admitted yet that its model is not up to scratch — and huge differences in forecasts persist.

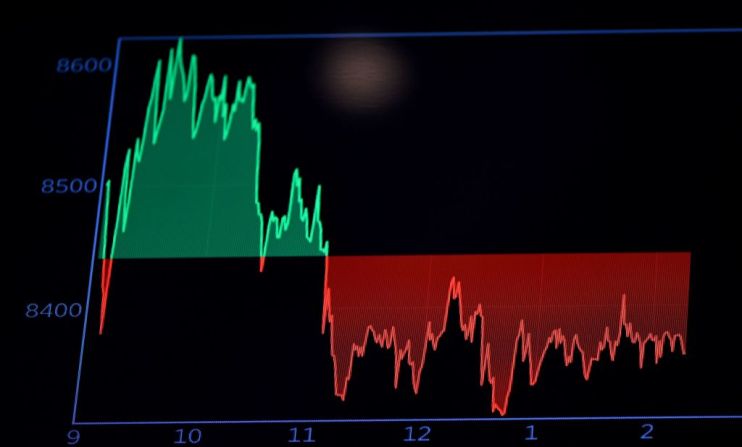

Main image credit: Getty