Environmental taxes: Will the Chancellor break with history, raise fuel duty and go further?

Looking to the manifesto, it would be hard to predict what the Budget would contain on environmental taxes. In common with the other main political parties, there were few direct commitments among the rhetoric. Beyond a statement on plastics packaging tax, we saw only a promise to “prioritise the environment in the next Budget, investing in the infrastructure, science and research that will deliver economic growth, not just through the 2020s, but for decades to come.” Combined with the fact that the UK is now hosting November’s 2020 United Nations’ International Climate Change conference (COP26) in Glasgow, this has increased expectations.

However, dig a bit deeper, including into what was said before the election, and the ambition needed in tax to deliver on environmental promises becomes clearer.

The UK’s history

Although the UK’s CO2 emissions peaked in 1973, emissions are generally measured against the level in 1990. On this basis, they have declined by around 44%, to levels last seen in the 1880s, delivering a decline that is faster than in any other major developed country. Particularly in the last decade, the shift towards renewable energy generation and lower electricity use has been substantial.

This success may seem odd to those who have followed the UK’s rather chequered history regarding environmental taxes, as such initiatives have had a mixed history.

The UK first made a legal commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1992. Tax measures with, at least in part, environmental objectives, along with statements of intent around the use of environmental taxation, followed over the next decade. Notably, vehicle excise duty and company car tax rates were linked to the emissions ratings of vehicles, climate change levy was imposed on business and landfill and aggregates taxes were successfully introduced. Higher landfill taxes have coincided with extraordinary reductions in landfill volumes.

But there have been political challenges when rebalancing the UK’s tax system towards environmental taxation. One of the more well-known taxes introduced, over a quarter of a century ago, was the intended increase in the rate of VAT on domestic heat and power to the standard rate, then at 17.5%. While the government took the first step to raise the rate to 8% with a view to increasing subsequently to the full rate, in the event the political backlash was sufficient to stymie the plan and the rate was subsequently reduced to the lowest allowed under the EU rules, being 5%. A similar story can be told with the green tariffs that were imposed on domestic bills… until these became politically toxic and were similarly removed.

And finally, perhaps the poster child for such stalemate, fuel duty has been frozen for the last nine years, resulting in a real-term decrease in taxation, something that remains a controversial topic. The freeze of duty in 2019-20, in the 2018 Budget, cost the Exchequer £840m in that year and increasing with inflation each year thereafter.

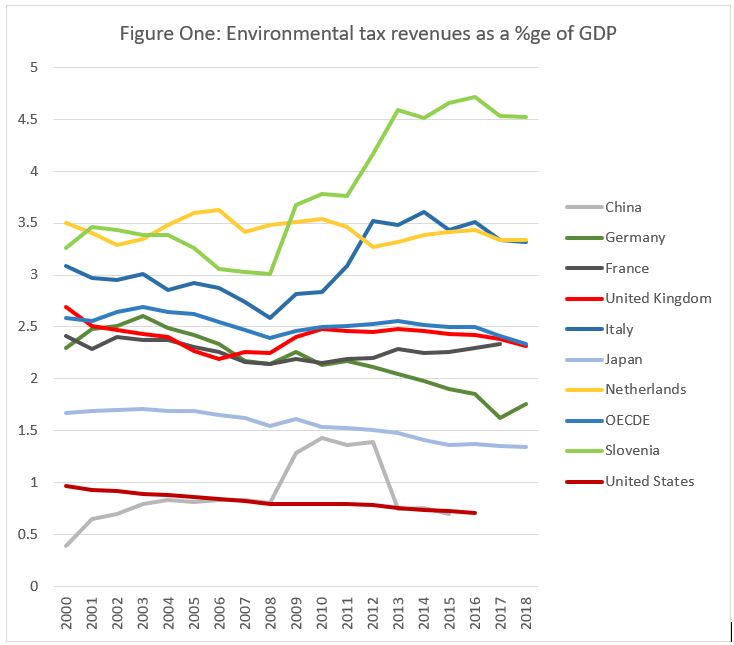

It is perhaps not surprising, then, that the UK’s environmental taxes are not world leading, with total revenue raised from environmental taxes, including taxes targeting emissions reduction, being in the mid-range for a European country, although above the OECD average. As can be seen from the figure below, this measure has been largely stable, with energy, transport, pollution and resources taxes remaining within a band of between 2.2% and 2.8% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) over the last two decades.

The scale of the challenge

With the apparent popularity of climate change action, perhaps the policy environment today is sufficiently different to overcome the negative reactions that were seen with VAT, green tariffs and fuel duty. It may well need to be, as in June 2019 the last government enacted a commitment to reaching net zero greenhouse gas emissions (Net Zero) by 2050. The Committee on Climate Change (the CCC), the UK Government’s official adviser on progress, has commented that:

“The required annual rate of emissions reduction for Net Zero is 50% higher than under the UK’s previous 2050 target and 30% higher than has been achieved on average since 1990.”

The scale of transformation needed to meet this target is enormous and tax policy, a key mechanism for changing behaviour, is almost certainly a tool that the government is going to need to deploy.

Challenges for environmental taxation for 2020

This year is going to be a critical one, with the Government having accepted the CCC’s recommendation to review how to fund the transition to Net Zero and HM Treasury scheduled to publish a report in autumn 2020 setting out principles to guide decision making during the transition. This review could provide the ideal basis for an integrated assessment of the full range of policy levers, including carbon pricing, taxes, financial incentives, public spending, regulation and information provision. It will likely be published in the run up to COP26 in November, which is expected to attract up to 30,000 delegates. COP26 is intended to promote an agreed international response to the climate emergency and, as host, the UK will want to show its progress towards Net Zero.

In policy terms, commentators such as the CCC note that the UK’s move towards Net Zero over the coming decades is likely to demand: continued steps towards electrification of the vehicle fleet, changes in power generation (more offshore wind farms?), shifts in domestic heating away from gas, and potentially changes to our diets (less meat?) and to land use patterns. Tax incentives or deterrents are likely to play a part in these moves, and it will be important that the role of tax is considered alongside the other means of intervention and not seen as the default option.

Tax raising?

Beyond the need to change behaviour (arguably the primary aim of environmental taxes), the Government may also look to such taxes to raise funds for spending on other priorities. Indeed, the Conservative and Liberal Democrat Coalition’s definition of environmental taxes excluded fuel duties, presumedly on the basis that these taxes have a role beyond that of addressing the environment. With the above shifts in behaviour away from petrol and diesel transport, the government is going to be faced with a significant hole in Exchequer revenues as fuel duties decline. So we may well expect to see further shifts in policy, from taxing fuel to taxing distance, and from taxing pollution to taxing congestion, potentially going well beyond the levels needed to capture the negative externalities.

What’s next

The Government is relying on these incentives and deterrents to change behaviour. So taxpayers and businesses would be well advised to keep an eye out for the policy declarations in this area, both in terms of increases in environmental-harmful areas and reductions and incentives in areas of environmental benefit. Long-term contracts premised on the taxation regime of today may well be costly mistakes when faced with rapid change and potentially penal regimes designed to engender behavioural responses. Similarly, businesses focussed on reinforcing climate-friendly behaviour may well find themselves delivered a fillip.

Climate change is on its way and so is tax policy change. March’s Budget may be the next step on a long journey.

The original version of this article appeared in the ICAEW’s TAXline.