Is the concept of the ethical CEO too good to be true?

“A fish rots from the head down.” It’s a worn cliché, perhaps, but one that resonates strongly in a world where increasing scrutiny is being placed on those at the helm of global companies.

Investors, customers, governments, and even chief executives themselves, are finally starting to take real action based on the idea that unethical conduct starts at the top and trickles downward.

For their part, chief executives at the world’s biggest companies have made declarations and promises, signalling a shift away from the pursuit of profit at any means towards more ethical, sustainable business practices.

Last year saw the highest rate of top bosses leaving their positions, with nearly 17.5 per cent of chief execs from the world’s 2,500 biggest companies departing their jobs, according to PwC’s consulting arm Strategy&.

And for the first time in the study’s history, more chief executives were dismissed for ethical lapses than for financial performance.

One way to view this is as a positive sign that boards and other stakeholders are holding chief executives accountable for ethical failures.

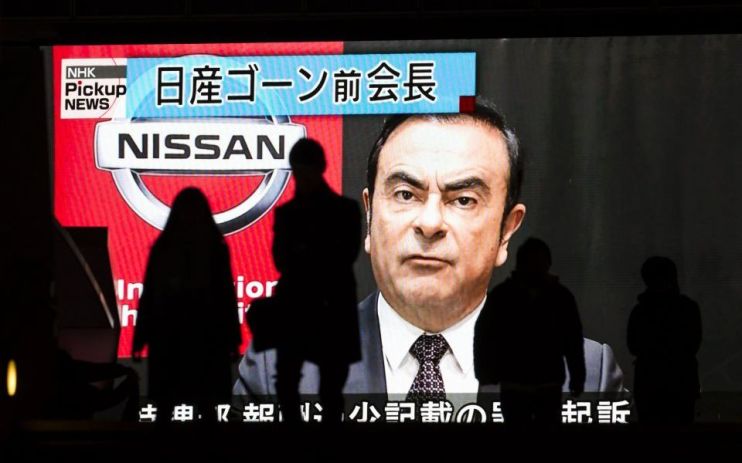

However, looking at the Strategy& numbers a different way, could there simply be more instances of serious ethical misconduct happening at big companies which have led to career-ending scandals? Indeed, the recent cases of Nissan, Toshiba, Wells Fargo, Arcadia, Volkswagen, Odebrecht, and Petrobras (to name a few) have been marked by shocking allegations that do not engender confidence in the state of corporate leadership.

In some of these instances, personal behaviour like misuse of company assets was directly to blame.

However, more often, the public outcry has taken aim at the boss’s willingness to tolerate misconduct, such as fraud or corruption by their subordinates. With such cases piling up in the headlines, it is fair to ask whether the concept of the ethical chief executive is too good to be true.

Reassuringly, just as chief execs have the power to tarnish the reputations of the organisations they lead, they also have the power to prevent cultural decay – and to transform companies that have been damaged by scandals. However, achieving this goal isn’t easy or intuitive. It requires some major changes to the way corporate leaders are selected, evaluated, and rewarded, as well as a new approach to how they lead their organisations.

Corporate boards have a big role to play. More often than not, they could do a better job keeping a critical eye on high-performing chief execs, holding leaders accountable for unethical actions, and asking tough questions about allegations and other problem indicators when they arise.

Top bosses themselves need to communicate their ethical expectations to their teams, customers, business partners, and even competitors. They should encourage open dialogue on ethical dilemmas among employees. Business practices should never be a taboo subject within the organisation.

They must also foster a culture where employees feel empowered to speak up about their concerns without fear of retaliation.

And beyond the four walls of their companies, they should participate in industry-wide collective action initiatives and stand with their corporate peers to tackle pervasive issues that are impossible to address alone.

Through better oversight, communication, and collaboration, chief executives can set a new standard for corporate leadership. The old adage about rotting fish need not apply here.