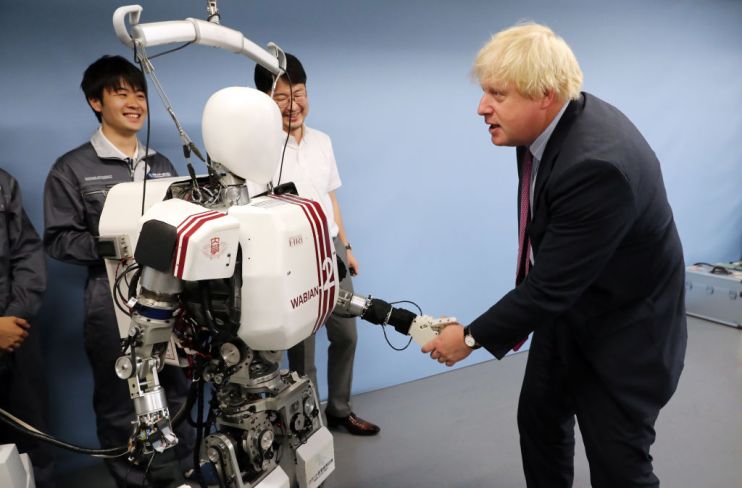

What does Britain need? More robots

On Monday, the Queen’s Speech set out the government’s legislative plans, starting with tackling all things Brexit, before laying out a radical programme to shake the country out of its current torpor.

Leaving aside whether any of this legislative programme manages to get through parliament, I would argue that one of the most critical issues has already been uncovered.

Just under a month ago, the Select Committee for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (Beis) concluded that: “The problem for the UK labour market and our economy is not that we have too many robots in the workplace, but that we have too few.”

Given the seismic events that have become the everyday backdrop to our news agenda these days, it’s no great surprise that this seemingly counterintuitive conclusion sneaked under the radar a bit. But the consequences of ignoring the Beis recommendations will be just seismic for us as a country as anything EU-related, particularly in a post-Brexit environment.

The UK has a serious productivity issue and will be stuck in the slow lane for decades to come if we don’t sort it out. All the evidence shows that the UK’s slow pace in moving to automation – we lag well behind our G7 competitors in our adoption of robots – has allowed other countries to steal a march, seizing upon the opportunities for jobs and economic growth.

The UK had just 10 robots for every million hours worked in 2015. Compare that to 131 in the US, 133 in Germany and 167 in Japan – nearly 17 times as many.

There remains the popular misconception that robots will “take our jobs”, when in fact the reverse is true. Those countries that have the most robots per worker actually have very low levels of unemployment. Robots are used to do dirty, dangerous and repetitive tasks, allowing humans to get on with more high-value operations.

So why has the UK has been slow to adopt robots compared with our industrial competitors? Obviously a multitude of factors are at play, but there are three key ones: businesses don’t yet understand the potential of automation, the environments in which businesses operate aren’t conducive to adopting new technology, and there is a worrying lack of digital skills among the workforce.

These are the issues the UK needs to get solving – and quickly – if we are to get back into the race.

For a start, as a matter of urgency, the government should develop a dedicated robot and artificial intelligence strategy by the end of 2020 to improve automation adoption, educate people on the potential benefits, and support British industries in their efforts.

Robotics needs to be at the front and centre of the UK’s industrial strategy, not tacked on at the end like an afterthought. The government is going to have to be far more ambitious if we are to succeed as a country, by actively incentivising business investment in productivity-boosting technologies such as automation.

The Made Smarter Commission, designed to give SMEs access to specialist advice to assess operations and develop a digitalisation strategy, along with 50 per cent grant funding for technology investments, has up to now been piloted in the north west region of the country – with some excellent results. It must now be rolled out across the UK as quickly as possible.

And in this fast-changing world, we will all need to be far more nimble when it comes to training than has previously been the case. This has to be a team effort. Businesses should be responsible for upskilling their workers as jobs change, whether through automation or other developments, but there is also an important role for the government to play in ensuring that everyone can develop the skills they will need to adapt.

It is probably too late for the UK to lead the robot revolution – we are simply too far behind. But we must begin to catch up, so that businesses up and down the land can feel the benefits of automation, and the economy can start to perform to its potential.

Main image credit: Getty