55 years of hurt: the connection between investing and football

In July, the England men’s football team reached their first major final since 1966. 30 years of hurt has become 55 years of hurt. Just one of many unwelcome statistics that have dogged the national team over the years, and which they hope to soon put an end to. The earlier England-Germany match provided a field day for statistical punditry. Every newspaper article and TV presenter trotted out the line that England hadn’t beaten Germany in a knock-out match since 1966.

English players on the losing sides from matches in Italia 90, Euro 96, and the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, were rolled out to comment on how hard it is to beat the Germans in tournament football.

And, as if to nail the point home, one British newspaper led with the fact that England had only won one knock-out match at a European championship in the previous 53 years (a penalty shootout victory against Spain at Euro 96).

Football has never been more awash with statistics. But some are more useful than others. Should any of these ones matter? Why should the performance of a team 25 years ago at Euro 96 have any bearing on who wins this latest encounter?

The long-term historical “track record” is irrelevant in terms of which team has more ability, is better organised, is in better form, or is more physically fit on the day of the match. It is, after all, an entirely different set of players for both sides than it was in the past.

England went on to beat Germany, thereby demonstrating what we are frequently told is true in the investment world – that past performance is not a guide to the future and may not be repeated.

Parallels with investing

There is a wider point here. Whenever you carry out any long term analysis, you need to be aware of how comparable, or not, today is with the past.

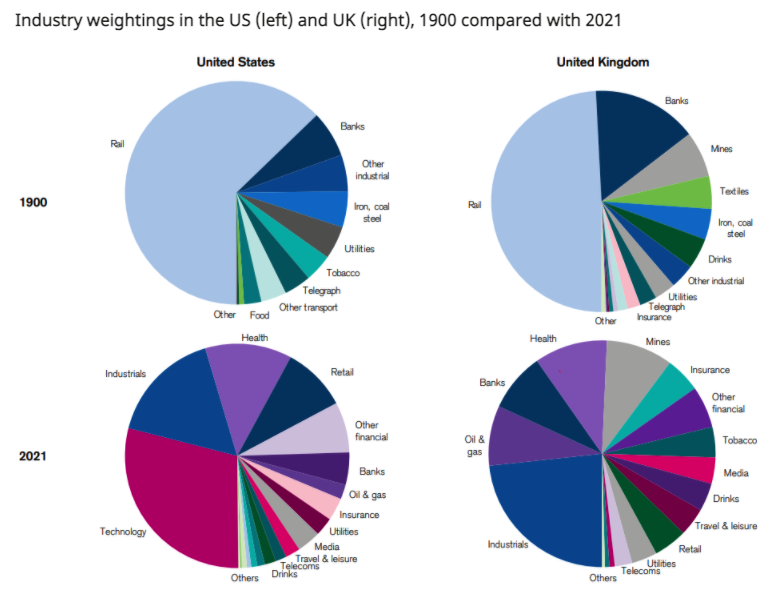

Just as today’s crop of English players are different to Gary Lineker’s 1990 team, the companies on the stock market today are entirely different to those of the past – a point which applies to other asset markets too.

I am a sucker for a long-term data set and one of the best is Professor Robert Shiller’s data on the valuation of the US stock market. It stretches all the way back to the year 1871. But how comparable are today’s technology titans to the railroad companies which dominated the US stock market back then?

Technology, especially software, can be scaled to large numbers of users around the world for very marginal cost. Sometimes all you need is a place on an app store. With the flick of a switch, the global marketplace can become available.

It would have been an entirely different story for a railroad company. Expansion would have relied on significant capital investment, labour and time.

Would you expect these companies to trade on the same valuation multiples? Clearly not. Then why does it make sense to compare the valuation of today’s stock market with where it was in the early 1900s?

This doesn’t mean long-term analysis is a waste of time. But it does mean that you need to be aware of its limitations.

One thing is timeless

Another reason why long-term analysis can still have value is that one thing is timeless, and that is human behaviour. Fear and greed are as old as time.

Railroads may be fundamentally different to technology companies, but they were very much the “hot stocks” of their day. This quote refers to the railway mania in the UK in the 1800s:

“In late 1845, railway ads covered over half the space in many papers. Such ads were awash with inflated claims, optimistic revenue projections and questionable accounting practices, whipping up euphoria among investors.”

Some railroad investors made huge profits but many others were taken in by frauds and scams.

Something similar was happening in the US, where excessive optimism resulted in over-supply and an eventual bust, sending around a quarter of the railroads into bankruptcy in 1894.

Railway mania, tulipmania, the dotcom bubble – history is littered with examples where investor exuberance has pushed prices too high relative to their fundamental value. The reverse is also true. During times of panic, markets go into freefall, as happened last year. This leads to an overshoot in the opposite direction.

There are, of course, many more examples of a less extreme nature.

The human machine is hard-wired to respond to emotional triggers. Knowing that we have behavioural biases doesn’t make it any easier to avoid the traps they lay for us (maybe you’re an exception but, y’know, over confidence…).

The timelessness of the human response is another reason why understanding how investors acted in the past can be useful for assessing markets today.

It’s also the one reason why hysteria around past football results can influence results today. The fundamentals are totally different but the psychology is not. Headlines around past failures can weigh on players minds. Continually reminding them of it hardly helps.

Fortunately, today’s players have psychologists to help them with this side of things. Similarly, I have always believed that this is an area where a financial adviser can have a big impact on an individual’s investment outcome.

These advisers, the coaching team, and the players will have their work cut out if England are to break free of their track record of 55 years of hurt.

– For more visit Schroders insights and follow Schroders on twitter.

Topics:

Important Information: This communication is marketing material. The views and opinions contained herein are those of the author(s) on this page, and may not necessarily represent views expressed or reflected in other Schroders communications, strategies or funds. This material is intended to be for information purposes only and is not intended as promotional material in any respect. The material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. It is not intended to provide and should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in this document when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. The value of an investment can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed. All investments involve risks including the risk of possible loss of principal. Information herein is believed to be reliable but Schroders does not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Some information quoted was obtained from external sources we consider to be reliable. No responsibility can be accepted for errors of fact obtained from third parties, and this data may change with market conditions. This does not exclude any duty or liability that Schroders has to its customers under any regulatory system. Regions/ sectors shown for illustrative purposes only and should not be viewed as a recommendation to buy/sell. The opinions in this material include some forecasted views. We believe we are basing our expectations and beliefs on reasonable assumptions within the bounds of what we currently know. However, there is no guarantee than any forecasts or opinions will be realised. These views and opinions may change. To the extent that you are in North America, this content is issued by Schroder Investment Management North America Inc., an indirect wholly owned subsidiary of Schroders plc and SEC registered adviser providing asset management products and services to clients in the US and Canada. For all other users, this content is issued by Schroder Investment Management Limited, 1 London Wall Place, London EC2Y 5AU. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.