29 reasons not to invest in the stock market

Wars, disasters, economic strife and political instability have been persistent themes over the last three decades and they can affect people’s attitude towards investing.

In many cases they make an already tough decision to part with your money and invest even harder, leading some to not invest at all.

Behavioural scientists have a name for this: loss aversion. They estimate that the psychological pain of losing is about twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining, hence why some people shy from the risks involved with investing.

Yet as Schroders’ research shows, staying out of the stock market over the last 30 years could have proven costly.

The eroding effects of inflation and historically low interest rates would have eaten away at the value of your money if you decided not to invest.

While investing in the stock market carries greater risks, such as the possibility of your losing all the money you have invested, and the value of the money you have invested going up and down it could have boosted your returns.

Of course choosing to invest depends on your personal circumstances and if you are unsure as to the suitability of any investment speak to an financial adviser

Schroders research found, after adjusting for the effects of inflation:

- £1,000 hidden “under the mattress” at the start of 1989 would now be worth £467 due to the effects of UK inflation – annual growth of -2.7 per cent.

- £1,000 left alone in a UK savings account at the start of 1989 would now be worth £1,011 – annual growth of 0.03 per cent.

- £1,000 invested in the FTSE All-Share index at the start of 1989, with all income reinvested, would now be worth £5,683 – annual growth of 11.2 per cent.

These figures are not adjusted to include any account charges or investment fees.

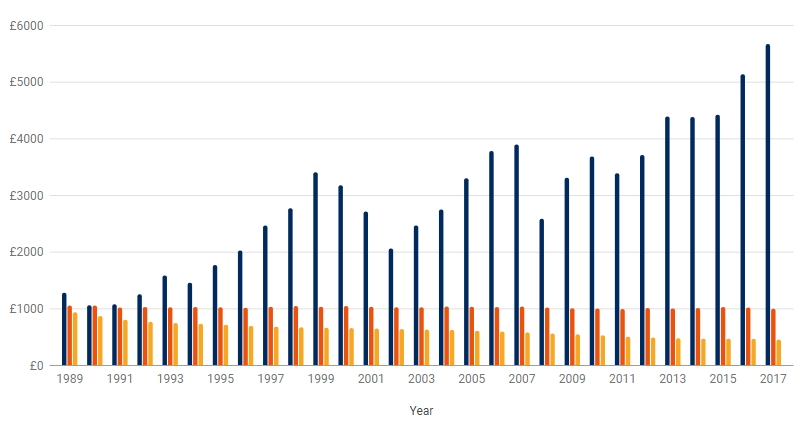

The chart below illustrates the change in real value each year of £1,000 invested in UK stocks, a UK bank account or left under your bed.

Please remember that past performance is not a guide to future performance. Investing in one geographical region [UK equities] may result in large changes to the value to your investment, which may adversely impact the performance.

In some circumstances, up to £85,000 in a UK bank account is protected by the Financial Compensation Services Scheme.

How the value of £1,000 could have grown (and shrunk) since 1989

This material is not intended to provide advice of any kind. Information herein is believed to be reliable but Schroders does not warrant its completeness or accuracy.

Source: Schroders. Refinitiv data for The FTSE All-Share Index correct as at 19 November 2018.

A short history of stock market crashes since 2000

The last 30 years have included some of the biggest stock market crashes in history.

In 2001, the FTSE All-Share index fell by 13 per cent. It was in the wake of the bursting of the “dotcom bubble” at the end of 1990s, when highly-rated technology stocks were sold off. But it also coincided with the devastating attacks on the World Trade Centre in New York in September. The period also saw a global economic slump, although the UK managed to avoid recession. The FTSE All Share index was down 22 per cent in the year to the end of 2002.

The global financial crisis of 2008, which began with the gradual collapse of the housing market in the US the year before, led to the worst global recession since the 1930s. In the year to the end of 2008 the FTSE All-Share was down 30 per cent, its worst annual performance since 1989.

The table below illustrates how your investment returns could have built up year by year between 1989 and 2017 and shows the damaging effect inflation can have on your wealth. It also shows global events that could have deterred investors in any of those given years.

Returns on £1,000 year by year since 1989

| Year | A reason not to invest? | UK stocks level – end of year (EoY) | UK stocks year-on-year % change | Average savings rate | Average inflation rate | Value of £1,000 invested in UK stocks (EoY) | Value of £1000 left in savings account (EoY) | Value of £1,000 stuffed under your mattress (EoY) |

| 1989 | Junk bond crisis | 761 | 36.1% | 12.0% | 5.2% | £1,291 | £1,068 | £948 |

| 1990 | Recession | 687 | -9.7% | 13.6% | 7.0% | £1,074 | £1,066 | £882 |

| 1991 | India economic crisis | 830 | 20.8% | 10.6% | 7.5% | £1,091 | £1,033 | £815 |

| 1992 | UK pulls out of the ERM | 1000 | 20.5% | 8.2% | 4.3% | £1,268 | £1,042 | £780 |

| 1993 | Swedish banking crisis | 1284 | 28.4% | 5.7% | 2.5% | £1,596 | £1,036 | £761 |

| 1994 | Balkan War | 1209 | -5.8% | 5.4% | 2.0% | £1,471 | £1,039 | £746 |

| 1995 | Tequila Crisis | 1497 | 23.9% | 5.6% | 2.7% | £1,783 | £1,035 | £726 |

| 1996 | Fed chairman questions stock market valuations | 1747 | 16.7% | 4.5% | 2.5% | £2,037 | £1,028 | £708 |

| 1997 | Asian crisis | 2159 | 23.6% | 5.5% | 1.8% | £2,480 | £1,044 | £695 |

| 1998 | Russian financial crisis | 2456 | 13.8% | 6.3% | 1.6% | £2,782 | £1,057 | £684 |

| 1999 | Argentine economic crisis | 3051 | 24.2% | 4.7% | 1.3% | £3,419 | £1,044 | £675 |

| 2000 | Dotcom bubble | 2870 | -5.9% | 5.5% | 0.8% | £3,190 | £1,058 | £670 |

| 2001 | Twin towers terrorist attack | 2489 | -13.3% | 4.6% | 1.2% | £2,726 | £1,047 | £662 |

| 2002 | Stock market crash | 1924 | -22.7% | 3.7% | 1.3% | £2,074 | £1,038 | £653 |

| 2003 | War in Iraq | 2326 | 20.9% | 3.7% | 1.4% | £2,478 | £1,038 | £644 |

| 2004 | Terrorist attack in Madrid | 2624 | 12.8% | 4.6% | 1.3% | £2,763 | £1,048 | £636 |

| 2005 | London bombings/Hurricane Katrina | 3203 | 22.0% | 4.9% | 2.1% | £3,315 | £1,045 | £623 |

| 2006 | Housing bubble | 3739 | 16.8% | 4.7% | 2.3% | £3,793 | £1,041 | £608 |

| 2007 | Sub-prime mortgage crisis | 3938 | 5.3% | 5.6% | 2.3% | £3,907 | £1,051 | £594 |

| 2008 | Global financial crisis | 2760 | -29.9% | 5.1% | 3.6% | £2,597 | £1,034 | £573 |

| 2009 | Global recession | 3591 | 30.1% | 2.2% | 2.2% | £3,323 | £1,020 | £560 |

| 2010 | European sovereign debt crisis | 4112 | 14.5% | 2.8% | 3.3% | £3,695 | £1,016 | £542 |

| 2011 | Greek debt crisis – bailout | 3970 | -3.5% | 2.8% | 4.5% | £3,403 | £1,005 | £518 |

| 2012 | US heads towards the fiscal cliff | 4458 | 12.3% | 2.8% | 2.8% | £3,725 | £1,023 | £503 |

| 2013 | Russia invades Ukraine | 5386 | 20.8% | 1.8% | 2.6% | £4,404 | £1,016 | £490 |

| 2014 | Brazilian economic crisis | 5449 | 1.2% | 1.5% | 1.5% | £4,392 | £1,025 | £483 |

| 2015 | China stock market crash | 5502 | 1.0% | 1.4% | 0.0% | £4,433 | £1,040 | £483 |

| 2016 | UK votes to leave the European Union | 6424 | 16.8% | 1.2% | 0.7% | £5,147 | £1,033 | £479 |

| 2017 | Rise of populist vote | 7266 | 13.1% | 1.0% | 2.7% | £5,683 | £1,011 | £467 |

Please remember that past performance is not a guide to future performance and may not be repeated.

Source: Schroders. Refinitiv data for the FTSE All Share total return index, which includes dividends. Inflation numbers supplied by the Bank of England. Savings data from Building Societies Association and http://www.swanlowpark.co.uk/savings-interest-data.

Nick Kirrage, a fund manager and author on the Value Perspective investment blog, has written often about the danger fear can play.

“People can lose touch with just how bad things have looked and been in the past,” he said. “That can lead to them taking – or failing to take – actions that can harm their personal wealth for decades to come.

“This data shows that investors who had instead opted to stay in cash would have seen their savings destroyed by inflation during a period when the stock market rallied. Quite frankly, there are many other periods of the last century which offer the same conclusion. Even the Second World War offered decent stock market returns in the US and UK.

“The reality is that there is no ‘perfect’ time to put money into the stock market. If you are holding out for one, you are going to remain in cash forever and, over the longer term, you are likely to be materially worse off as a result.”

The opinions included above should not be relied upon and should not be construed as advice and/or a recommendation. Past performance cannot be relied upon as a guide to the future performance and the value of your money may fall when invested.

Important Information: This communication is marketing material. The views and opinions contained herein are those of the author(s) on this page, and may not necessarily represent views expressed or reflected in other Schroders communications, strategies or funds. This material is intended to be for information purposes only and is not intended as promotional material in any respect. The material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. It is not intended to provide and should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in this document when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. The value of an investment can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed. All investments involve risks including the risk of possible loss of principal. Information herein is believed to be reliable but Schroders does not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Some information quoted was obtained from external sources we consider to be reliable. No responsibility can be accepted for errors of fact obtained from third parties, and this data may change with market conditions. This does not exclude any duty or liability that Schroders has to its customers under any regulatory system. Regions/ sectors shown for illustrative purposes only and should not be viewed as a recommendation to buy/sell. The opinions in this material include some forecasted views. We believe we are basing our expectations and beliefs on reasonable assumptions within the bounds of what we currently know. However, there is no guarantee than any forecasts or opinions will be realised. These views and opinions may change. To the extent that you are in North America, this content is issued by Schroder Investment Management North America Inc., an indirect wholly owned subsidiary of Schroders plc and SEC registered adviser providing asset management products and services to clients in the US and Canada. For all other users, this content is issued by Schroder Investment Management Limited, 1 London Wall Place, London EC2Y 5AU. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.