Syriza’s plan for the Greek economy falls short: Grexit must not be ruled out

After the failure of the new Greek finance minister’s tour of Europe’s capitals this week to produce a workable debt deal, Greece’s situation now seems terminal. Greece has an unemployment rate above 25 per cent, a debt-to-GDP ratio of almost 200 per cent and deflation of 2.6 per cent. The country’s economy has shrunk by 23 per cent since 2008.

The big mistake of the Troika – the European Union, European Central Bank (ECB) and International Monetary Fund (IMF) – was to assume that “structural reforms” to the Greek economy, tied to massive bailouts in 2010 and 2011, would be enough to generate growth in the face of persistent deflation.

To be sure, those reforms were desirable. Labour market liberalisations have made it cheaper to hire and fire workers, boosting employment, and pension reforms have improved Greece’s long-term fiscal position.

Significant spending cuts were unavoidable, given the country’s debt burden. But here’s the problem: to avoid “bad deflation”, states must ease monetary policy in proportion to the spending cuts that they implement. This “monetary offset” is what has allowed the UK and US to grow, despite large budget cuts.

Since Greece does not control its own monetary policy, it has not been able to offset its cuts in this way, so its austerity programme really has hit the economy with deep deflation. That means more unemployment and, since most of the country’s debt is held in nominal terms, a larger relative debt burden.

Greece’s new government – a coalition of radical leftists, headed up by Syriza – pledged to tackle this. One possible reform floated this week by the country’s new finance minister Yanis Varoufakis would be to swap Greece’s debt to the ECB and EU governments with new debt linked to Greece’s nominal GDP, meaning that it would shrink in proportion to a shrinking Greek economy or deflation.

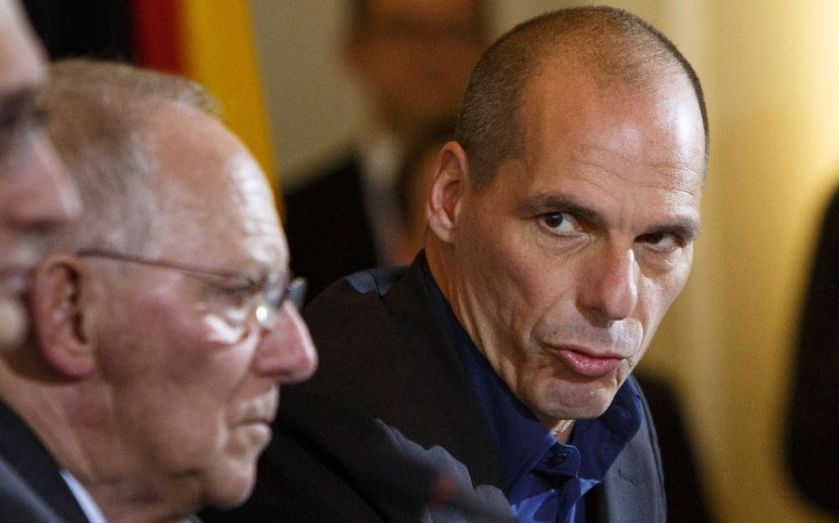

This plan would be a sensible move for Greece and the rest of the Eurozone. Greece’s ballooning debt problem would be brought under control, to some extent, making it less likely to default. But it appears to be a non-starter, with yesterday’s meeting between Varoufakis and German finance minister Wolfgang Schauble to discuss debt renegotiations ending in open hostility between the two who, according to Varoufakis, “didn’t even agree to disagree”.

In any case, this would not solve Greece’s underlying economic problems. Tight monetary policy by the ECB has led to extremely low inflation across the Eurozone, which has probably caused deflation all by itself in shrinking economies like Greece.

Although the ECB has now announced a quantitative easing programme, it is not open-ended or tied to the bank’s inflation target, making it severely limited. It may – just – be enough for the Eurozone as a whole, but it is definitely not enough for Greece.

In economic terms, the debt is largely a distraction. What Greece really needs is much, much easier monetary policy, including extra inflation to catch up to an old price level. It cannot get this while it is in the euro.

A Greek exit from the euro is something that even the country’s new Marxist leaders have refused to consider publicly. But it may be Greece’s last hope.

Sam Bowman is deputy director of the Adam Smith Institute.