2022: The year the UK economy soured

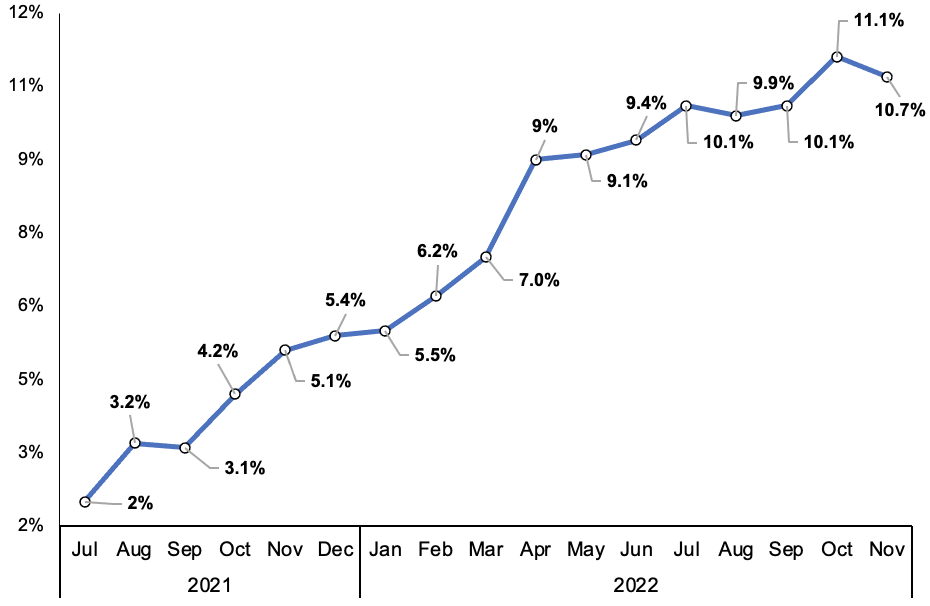

Let’s not forget that inflation was already a problem heading into 2022.

The final inflation reading of 2021 was for November and came in at 5.1 per cent, nearly three times higher than the Bank of England’s two per cent target and the highest level since September 2011, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

The initial price burst was driven by supply chains wilting under the weight of a sudden burst in demand after pandemic restrictions were scrapped.

Oil and gas costs also climbed due to countries competing fiercely for inventories to power their economies back to full strength. Storage constraints did not help.

Despite price pressures heating up, governor Andrew Bailey and the rest of the monetary policy committee (MPC) famously marched markets up a hill only to send them back down again at the November meeting when they decided to keep interest rates at a record low 0.1 per cent.

Loose monetary policy also supported demand. Consumers and businesses were able to borrow at record low rates until December 2021 when the Bank tightened (just 15 basis points) for the first time since 2018.

At that meeting, the Bank said it is committed to focusing on medium term inflation pressures “rather than factors that are likely to be transient”.

Well, those “transient” factors sent inflation this year to a peak of 11.1 per cent, a 41 year high, although this week’s figures sent a clear signal that it has now passed its peak. The Bank has a hand in reaching that peak by lifting interest rates nine times in a row to 3.5 per cent, the highest since October 2008.

Inflation started kicking higher at end of 2021

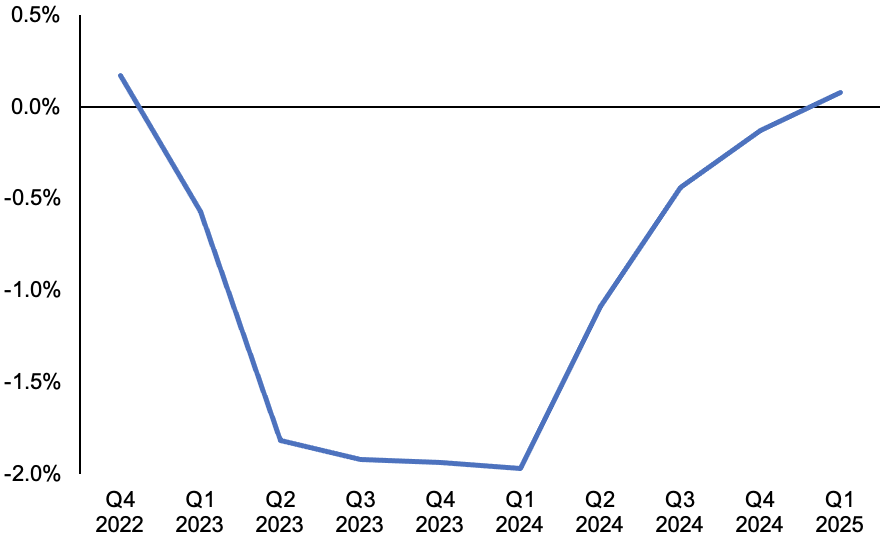

Nonetheless, the UK is clearly headed into a long (albeit shallow) recession lasting at least a year that the Bank thinks could shave nearly three per cent off GDP.

At the beginning of the year, just as Britain was emerging from Omicron curbs, the International Monetary Fund released new forecasts in January predicting the economy would expand 2.3 per cent in 2023. Now it expects just 0.3 per cent growth and a recession.

Hw did the country get in this state?

Supply chain breakdowns

Supply chain pressure at the beginning of 2022 was gripping businesses. The average cost of shipping goods was running at more than $9,000 in early January, according to Freightos’s Baltic Dry Index.

Households splurged electronics and other durable goods while cooped up in their homes amid the pandemic. While spending patterns partially returned to normal in the early months of this year, demand for physical products which the UK imports a lot of remained high.

As a result, supply chains “couldn’t really cope,” Alpesh Paleja, lead economist at the Confederation of British Industry (CBI), told City A.M.

Ongoing lockdowns in China also clogged up key trading arteries. Shortages followed, for consumer goods and raw materials, “harming production and sales at the same time as adding to input costs,” Sandra Horsfield, economist at Investec, told City A.M.

Businesses responded to swelling costs by rising prices, although Dean Turner, chief eurozone and UK economist at UBS Wealth Management, said Brits were “willing, and able, to absorb higher prices”.

Shipping costs jumped higher in 2021

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine

In February, UK inflation topped six per cent. And then Russia invaded Ukraine on 24 February and everything changed.

The human tragedy of the war will top any economic costs. But Putin’s decision to send troops into Kyiv has turbocharged inflation in every corner of the world – not just Britain.

Gas prices skyrocketed on fears Russia would suck supplies out of the market in response to western sanctions designed to freeze Putin out of the financial system. That is what happened.

Oil prices also surged partly due to weaker Russian supplies and countries hoovering up alternative energy sources to replace gas.

Energy costs have been pegged back by imports of liquified natural gas imports replacing Russian supplies, unusually warm weather curbing demand and China sticking to zero-Covid, although that may be coming to an end.

Nonetheless, the energy price surge has raised the price of UK imports, while the price of exports has not climbed as much, resulting in what economists call a terms of trade shock.

“We are now paying more for goods we import, especially energy. Incomes are rising at a rate slower than inflation. We are, as a country, poorer as a result,” Turner added.

While the war has made us poorer, “we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that the UK economy was not in a position of strength even as the conflict was brewing,” Frédérique Carrier, head of investment strategy at RBC Wealth Management, told City A.M.

Inflation in the UK climbed 2.8 percentage points from February to April to nine per cent from 6.2 per cent.

UK gas future price has been on an upward march all year

Fiscal chaos

Now policymakers, arguably, were unable to mute the impact of the aforementioned factors that have buffeted the UK economy this year.

The same cannot be said of the disaster that was British fiscal policy in the late summer and autumn.

The mistakes of Liz Truss’s mini-budget have been well catalogued. Launching unfunded tax cuts would have boosted household and businesses’ finances. But, doing so at a time when inflation is running at a 40 year high is reckless.

Similarly, now chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s decision to hike taxes and cut spending £55bn in last month’s autumn statement when the UK is headed into a recession is not the typical textbook response.

The most effective policy mix is probably somewhere in the middle.

Nonetheless, between Truss’s mini-budget on 23 September and Hunt’s statement on 17 November, UK fiscal policy underwent an around £100bn swing – very, very unusual.

Truss’s decisions will undoubtedly have the most immediate damaging impact on the UK. Banks were forced to raise mortgage rates after gilt yields fired higher on Truss’s borrowing splurge.

“For those households that had to refinance their mortgages in the immediate aftermath, this will have clearly exacerbated the squeeze on spending power,” Horsfield said.

This week the Bank of England predicted around 4m homeowners will have to absorb a £3,000 jump in their mortgage bills next year. Hunt’s tax rises will intensify that budget squeeze.

A combination of high inflation, taxes and mortgage rates eroding pay growth, which is running at nearly seven per cent in the private sector, far above the long term trend, will prompt Brits to slash spending and drive the coming recession.

Coming recession could be long and painful

2023, the year of the slow burning real income squeeze

Essentially, what happened to the UK over the course of 2022 was this: “The UK [has been] hit by a large terms of trade shock that [has pushed] inflation to its highest rate in 40 years and [driven] historic falls in real household disposable income,” the Office for Budget Responsibility summed up nicely in November’s forecasts.

The good news is that inflation will fall in 2023, likely to around four per cent next Christmas, but pay is unlikely to keep pace.

If 2022 was an “inflation centric” one, as Paleja said, then 2023 will be the year of the slow burning real income squeeze and recession. Buckle up.