2021 in review: Furlough is government’s big success story, but Rishi Sunak’s £69bn lifesaver comes at a price

Furlough has become a household word in recent years.

The scheme that protected the jobs of nearly nine million Britons at its peak has been hailed as the big success story of the Government’s Covid support measures as the jobs market rebounds at an impressive pace.

The warnings of soaring joblessness that struck fear into the hearts of many at the start of the pandemic have so far not come to pass, with the furlough scheme widely credited with having shielded the UK from mass redundancies.

Furlough was launched in March 2020 to help firms keep staff on and continue paying them during enforced closures when the country went into lockdown.

It paid 80 per cent of wages, up to £2,500 a month, with 11.7m jobs supported over the course of the scheme and 8.9m people on furlough at its peak.

By the time the scheme closed at the end of September, it cost the UK £69bn: an average of nearly £6,000 for each furloughed job.

The cost is staggering and the taxpayer ultimately has to foot the bill, but the economic shockwaves that would have been felt without it would have cost the UK far more, according to experts.

EY Item Club’s chief economic adviser Martin Beck believes the rate of unemployment could have soared to an unthinkable 20 per cent if no action had been taken.

Early days

In the early days of the crisis, even with furlough in place, the predictions were grim.

At one stage, the Office for Budget Responsibility forecasted that unemployment could reach four million – an eye-watering rate of 12 per cent.

As it turns out, joblessness is looking likely to have already peaked, having hit 5.2 per cent in the final quarter of 2020 and falling steadily since.

Joblessness is now almost back to the levels seen before the pandemic struck, at 4.2 per cent in the three months to October, although the latest wave of the pandemic could mean the rate edges higher as some stricken sectors suffer.

Beck said: “It is the smallest peak of any recession since the war. That’s proved positively that it worked.”

He said that in preventing widespread job losses, the scheme had successfully “avoided the long-term scarring effects of people losing their jobs and not being able to get back into work for a long time”.

He admits the Government had little choice, however, given that it was forced to shut down the economy in March last year.

“The damage would have been so great that it’s implausible it (furlough) would not have happened – any Government would have had to do something big if they were going to lock down.”

EY Item Club’s chief economic adviser Martin Beck

The speed with which the scheme got off the ground and the fact it was in place for so long saw the economy recovering strongly when workers came off it, with demand for workers rising at a blistering pace.

There were still just over one million people on the support when it came to a close at the end of September, but the latest official data suggests that, as of late October, 87 per cent of furloughed employees had returned to work.

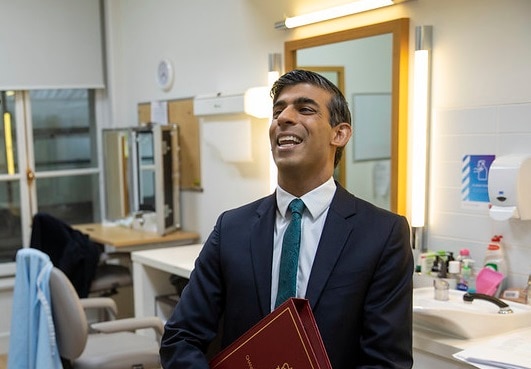

Chancellor Rishi Sunak has been roundly praised by economists and the likes of the International Monetary Fund for taking swift action with furlough and other emergency measures.

But there have been some bumps in the road, with Mr Sunak facing harsh criticism over delays to extending furlough last autumn as the UK entered the second lockdown, waiting until just days before the scheme was initially due to end, which saw firms lay off staff in anticipation.

“The lateness meant some people lost their jobs who didn’t need to,” said Beck.

Downsides

There have also been concerns over downsides of the scheme, with worries that some workers may have returned to jobs but on reduced hours and lower pay.

Another criticism is that while the scheme preserved jobs, it stopped workers from being reallocated to growing sectors.

The robust jobs figures also do not show the full picture of the UK labour market, with much of the increase in employment down to rising numbers of part-time workers and those on zero-hours contracts.

There is thought to be an army of missing workers relative to pre-pandemic times as many older employees have taken the opportunity to retire early, while a raft of younger people have chosen to go into education.

With the Government facing calls for furlough to be resurrected in a targeted form to help firms in sectors suffering amid the fourth wave of the pandemic, there are lessons to be learned for future schemes.

Not least to avoid the fraud seen in the early days when the scheme was rushed out.

HM Revenue & Customs’ initial estimates from September last year suggested around £3.9 billion of furlough payments were fraudulently claimed.

Few can dispute its success, but with the taxpayer set to be paying to recoup the cost of the scheme for many years to come, such policy tools are likely to be kept firmly in the Treasury’s box marked “emergency use only”.