| Updated:

Antibiotic resistance: Genome editor could provide the cure

The threat posed by antibiotic resistance to human health is growing. Every year, more bacterial strains emerge which are able to to resist even the most powerful drugs.

At the moment, roughly two million people are infected by drug resistant bacteria in the UK every year, leading to around 23,000 deaths.

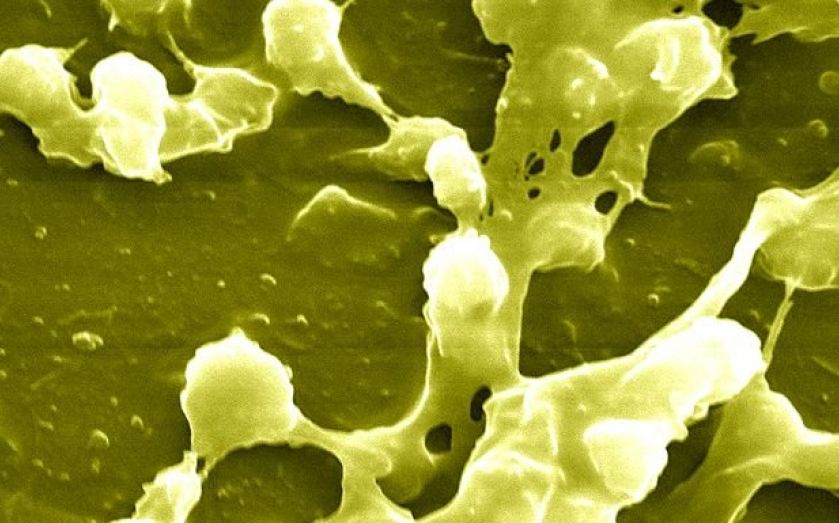

Traditional methods for killing bacteria involve interfering with specific parts of their life cycle, such as cell division and protein synthesis. But some bacteria have mutated their genes to prevent these processes from being identifiable to the drugs used to stop them – the result is that they are extremely proficient at evading recognition and so can easily multiply in the human body.

Scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have now developed a gene-editing technique, details of which were published in Nature Biotechnology, that may prove capable of ridding even the most evasive bacterial strains of their resistance.

Called CRISPR, it works by targeting and disabling the specific genes that confer resistance to the bacteria. Sections of the drug's gene-altering software are built to look for and alter these genes.

When they put the new technique to the test, they found that it was able to specifically target and kill more than 99 per cent of the resistant bacteria, while antibiotics to which the bacteria were resistant did not induce any significant killing.

In addition, the researchers showed that the CRISPR system could be used to selectively remove specific bacteria from diverse bacterial communities based on their genetic signatures, thus opening up the potential for "microbiome editing" beyond antimicrobial applications.

The researchers are now testing this approach in mice, and they envision that eventually the technology could be adapted to deliver the CRISPR components to treat infections or remove other unwanted bacteria in human patients.

Another technology, developed last month by researchers at the same lab, works by identifying combinations of genes that work together to make bacteria more susceptible to antibiotics.

Timothy Lu, lead researcher of both studies, hopes that a combination of these two technologies could lead to the development of new drugs to help fight the growing threat of antibiotic-resistant bacteria on a large scale.

"This is a pretty crucial moment when there are fewer and fewer new antibiotics available, but more and more antibiotic resistance evolving," he said. "We've been interested in finding new ways to combat antibiotic resistance, and these papers offer two different strategies for doing that."