Is there a cure for Ebola? These companies are trying to beat the virus

There is currently no licensed vaccine or specific treatment available for the deadly Ebola virus, but a handful of companies are racing to create a cure for the disease as it spreads across West Africa at an unprecedented rate.

Until now, the main barrier to developing an effective treatment has been a lack of potential financial gains. The parts of the world where Ebola is found tend to be very poor, which means treatments would most likely have to be given away for free and so would not benefit shareholders.

But as the disease gains momentum and the death toll rises – it had reached 805 as of 18 August, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO) – the pressure on companies to find a remedy is rising.

Earlier this month, the WHO described the problem in West Africa as “vastly underestimated” and unapproved treatments could be used without receiving official approval. But what are these treatments, and who is developing them?

Tekmira’s TKM-Ebola

One of the most promising treatments, TKM-Ebola, was able to protect against an extremely virulent strain of the virus when it was tested on monkeys, even if administered three days after initial infection.

The drug takes a genetic approach to tackling the disease, using small pieces of genetic material called interfering RNAs to meddle with the Ebola virus and stop it proliferating inside its victim’s cells.

Tekmira, the Canadian company behind the treatment, has now started a human safety trial. Tekmira is using $140m of funding from the US Department of Defence to develop the drug.

Fujifilm’s Favipiravir

In an unprecedented move for a company, Japan’s Fujifilm has bridged the gap between camera film maker and disease fighter.

An anti-flu pill created by one of its subsidiaries, Toyama Chemical Co, is thought to have the potential to fight the Ebola virus and is currently being tested on monkeys infected with the disease.

Once the tests are complete, which could happen as soon as September, US government researchers are hoping to get it fast-tracked through a regulatory review process and put it into action.

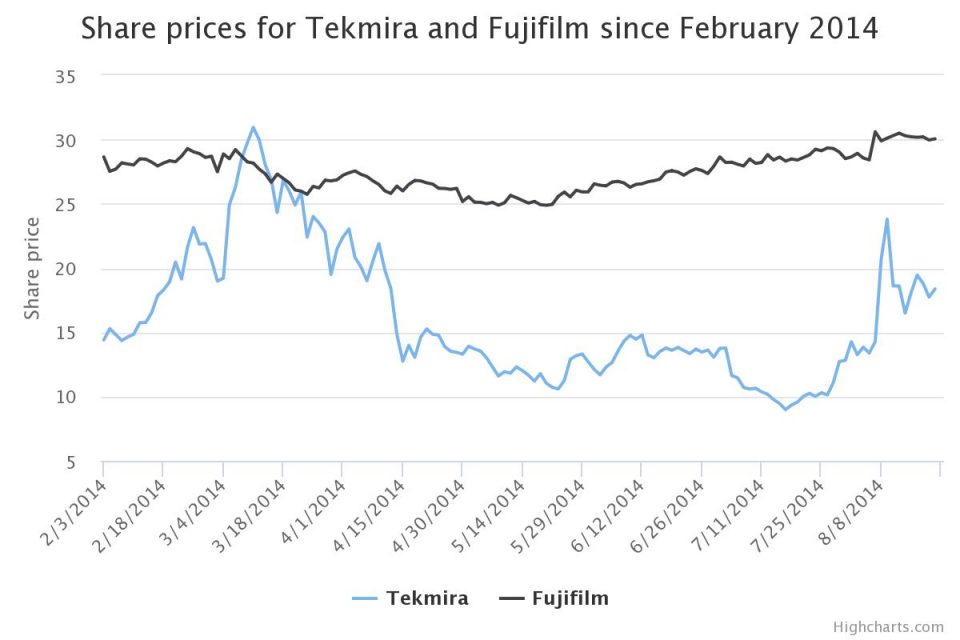

Following the news of Favipiravir’s potential use on 7 August, Fujifilm rose 5.4 per cent in Japanese trading. In fact, both Tekmira and Fujifilm have benefited from their drugs being fast-tracked.

On 11 August, Tekmira’s share price closed at a four-month high of $23.8 following the news US regulators had fast-tracked TKM-Ebola for use on humans. Although the price has fallen back slightly since, it is still benefiting.

The share price of Fujifilm, meanwhile, rose to $30.6 on 7 August, and has remained consistently high since then.

The graph below shows how the closing share price values for Tekmira and Fujifilm have changed since the epidemic first broke out in Guinea in February. Since then it has spread to Sierra Leone, Liberia and most recently Nigeria.

Mapp Biopharmaceutical’s ZMapp

Private company Mapp Biocharmacueutical is the only one to have used its treatment on humans suffering at the hands of the current epidemic.

ZMapp, a serum made up of three different types of antibody, was injected into two US aid workers and a Spanish priest, all of whom were infected with the Ebola virus. The aid workers survived but the priest did not. This reflects the not-so-high 43 per cent recovery rate observed during an earlier trial of the drug on monkeys.

Nonetheless, ZMapp has since been given to three doctors in Liberia, and all are showing “remarkable” signs of improvement, according to a government minister.

GlaxoSmithKline and the US Institute of Health

Last May, GSK purchased a small vaccine research company called Okairos for $325m. An early-stage vaccine has since been developed by the company as a preventative measure for Ebola.

The vaccine is currently undergoing pre-clinical trials, but it could be a long wait before it’s in use; GSK said “clinical development for a new vaccine is a long, complex process, often lasting 10 or more years”.

US Army’s BCX4430

The US Army medical research institute of infectious diseases has developed its own combatant to the Ebola epidemic.

BCX4430 is part of the “nucleotide” family of drugs. So far, tests on mice and macaque monkeys have proved successful, and human trials are due to take place next year.

It contains a structure in its genome which resembles something the Ebola virus would normally use when trying to grow inside our cells. If the virus accidentally uses the part of BCX4430 instead, this can be fatal as BCX4430 blocks Ebola’s further growth and reproduction.

But why has the army got involved? Because the virulence and high death rate (the most lethal strains can kill up to 90 per cent of their victims) of the Ebola virus make it a prime candidate for bioterrorism.

Gold nanotechnology

One of the problems with developing a vaccine for Ebola is that the virus mutates quickly, so targeting the rapidly-changing proteins found on its surface becomes a pretty tough task.

Scientists at the Northeastern University in Boston have potentially found a way to get around this problem by developing nanoparticles capable of stopping the Ebola virus from mutating and so kill it. They target the virus by attaching to its surface and altering its structure, so it can no longer enter cells to replicate.

The nanoparticles are made of gold. “We also are developing gold nanoparticles that can attach to Ebola, and other viruses, and then when we heat up the gold through infrared wavelengths, we can selectively kill the Ebola virus,” chief scientist Thomas Webster explained to Computerworld.

The downside is that Webster said he is probably five to 10 years away from having a nano-based treatment for Ebola, so it’s probably out of the running for now.

What is Ebola? And how is it spread? Here’s what you need to know.